The Science of Bias

The brain relies on shortcuts all the time.

We use what we’ve learned from our environment to make quick assumptions about whom to trust, how to behave, what to say.

But shortcuts can sometimes lead us astray.

You can’t always trust your brain.

A looping animation of a pair of shifty eyes looking around.

We’ve got

Mindbugs

Our eyes play tricks on us.

Our minds fill in the gaps of what we think we see.

But is that actually what’s there?

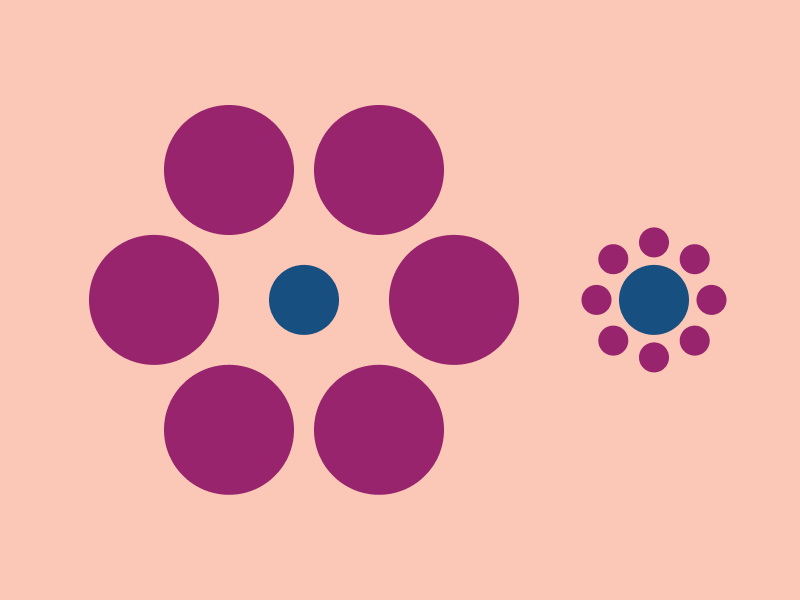

Check out the two blue circles.

They look like different sizes.

But look again!

A new perspective shows what they really are:

two identical circles.

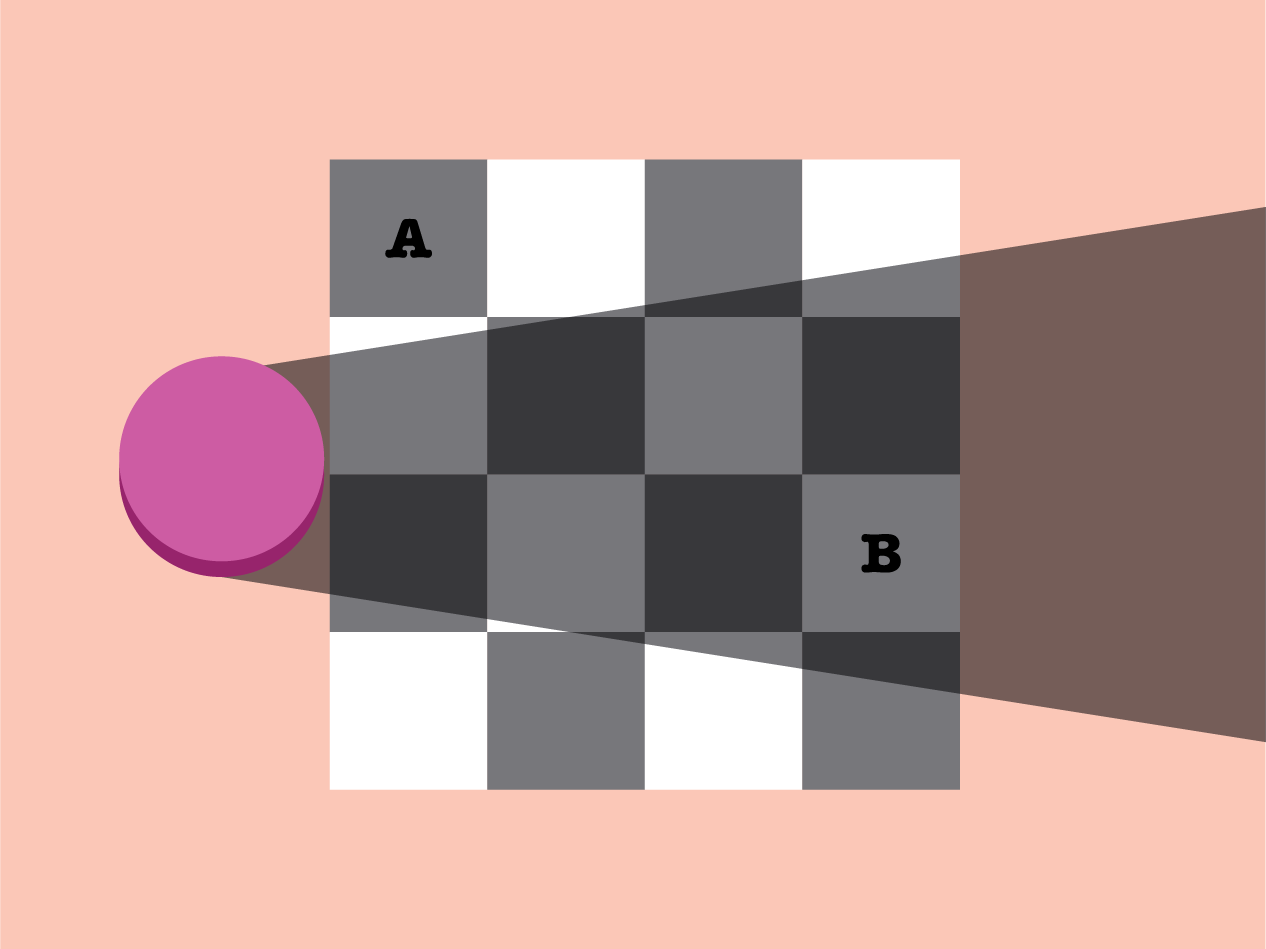

Now check out these two squares—A and B.

They look like different colors. A is darker than B, right?

But look again!

A new perspective shows what they really are:

two identical squares.

Two groups of circles appear on screen. The blue circle in the left group is surrounded with larger purple circles, where as the blue circle on the right is surrounded with smaller circles. The blue circle on the left appears to be smaller than the blue circle on the right. Two lines are drawn between the two circles, revealing that they are in fact the same size. The circles fade off screen. A checkerboard appears on screen and a cylinder casts a shadow on the checkerboard. Two of the squares are highlighted. Square A is surrounded with squares that are lighter color, where as square B is surrounded with squares that are darker color. Square A appears to be darker than square B. A line is drawn between the two squares, revealing that they are the same color.

Still don't believe your eyes?

These visual illusions work because the surrounding context of an image shapes what we see. Context is so powerful because it sets up our expectations of what we might see. And once we have that expectation, we can’t see it any other way!

Mindbugs are engrained patterns of thought that lead to errors in how we perceive, remember, reason, and make decisions.

Professor of Psychology, Harvard University

Listen In

From Mindbugs to Bias

What we think we see out there in the world is not always what’s really there.

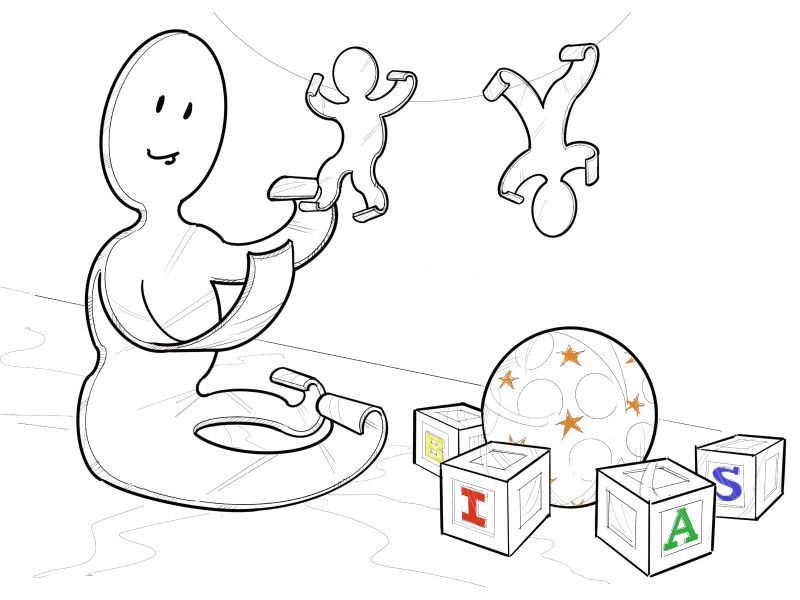

As infants, we discover who is safe and trustworthy by recognizing the types of people who surround us. We often see that we are surrounded by the people who look like us. Therefore, those types of people must be trustworthy.

But this is a mindbug just as much as seeing two identical blue circles as different sizes. Infant minds pick up patterns about people in the world, influencing their expectations of who is good or bad.

As we grow up, these early biases crystallize into two different forms. On the one hand, we have our implicit biases. These biases are automatic; they happen so fast we may not even notice them.

On the other hand, we have explicit biases. Explicit biases are more deliberate and controlled; biases that we are able and willing to talk about with our friends.

Throughout the rest of our lives, these implicit and explicit biases will be reinforced from our individual experiences and the people around us.

Bias is a process and builds over a lifetime.

Implicit bias is like the smog that hangs over a community. It becomes the air people breathe.

Journalist

Listen In

Practice Makes Perfect

We all know that practice makes perfect. This is true not just for riding a bike or learning to dance. It is also true of our biases.

Simply put: The more we use our biases, the deeper they go into our minds and our everyday actions. And we certainly use our biases a lot.

We use our biases to divide the “us”—the groups of people that are similar to us—from the “them”—the outsiders or others who may hold different ideas or identities.

Many times, the “us”‑ing is helpful. Being part of an “us” makes us feel safe. It makes us feel like we belong.

But the “them”-ing, the othering of outsiders, can be harmful when we’re not aware of it and aware of the consequences.

We tell ourselves stories about “them” to help us justify why we treat “them” differently. We tell ourselves stories with devastating consequences that lead to homophobia, racism, ableism, sexism, antisemitism, Islamophobia, and more.

Bias crystallizes from the repeated practice of separating "us" and "them."

Get Inside

Your Head.

What about my brain? Is there bias there too?

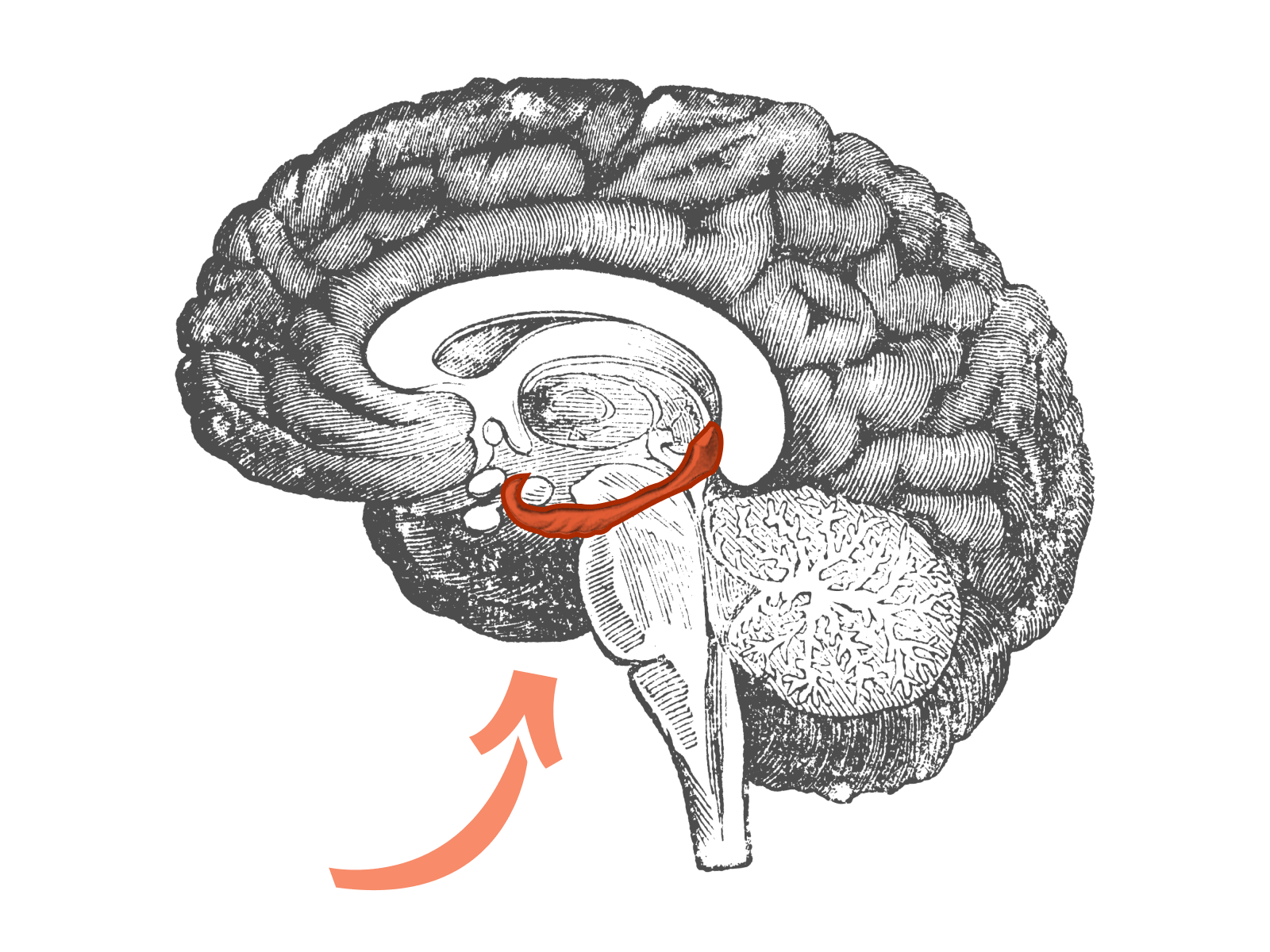

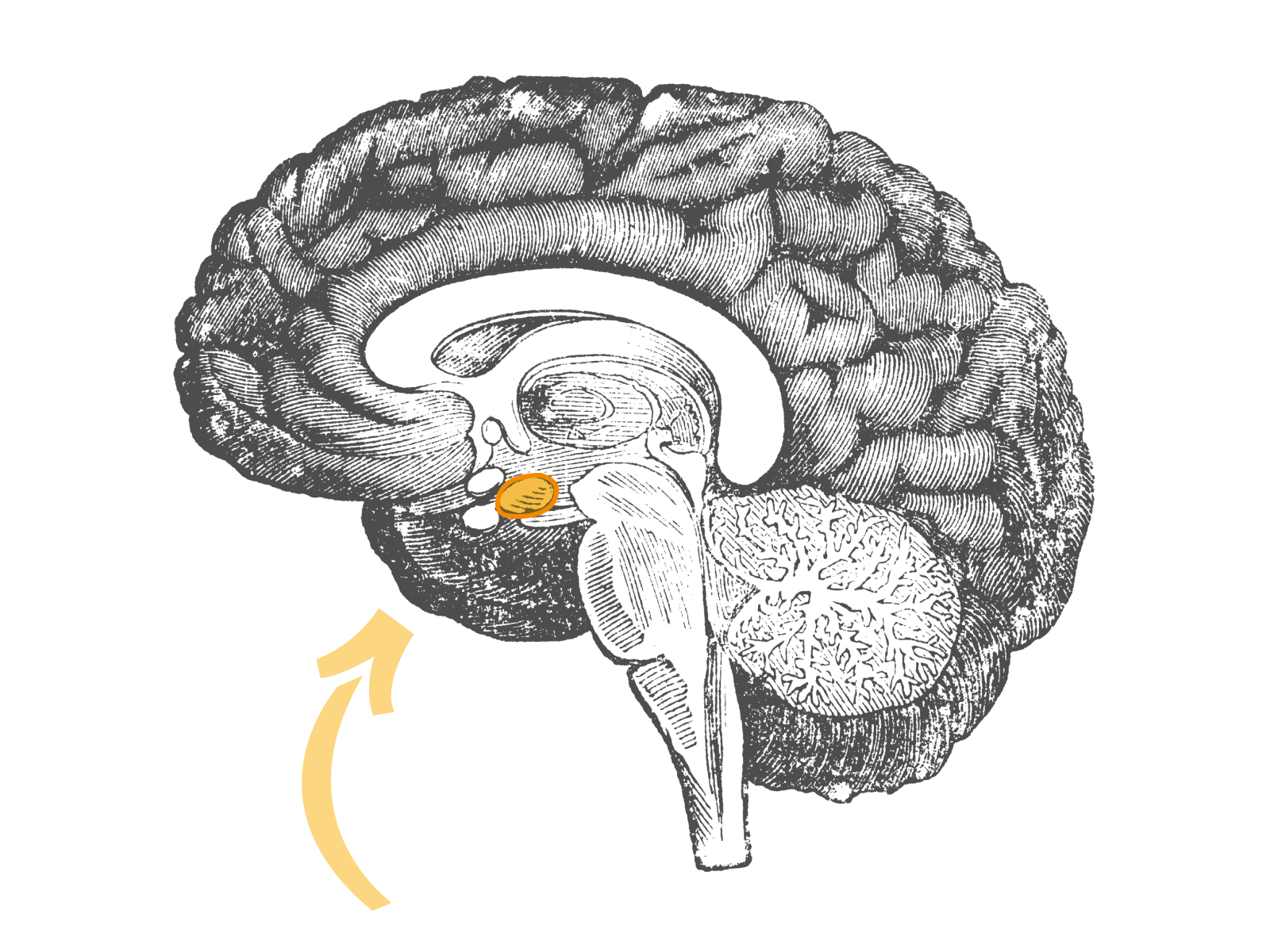

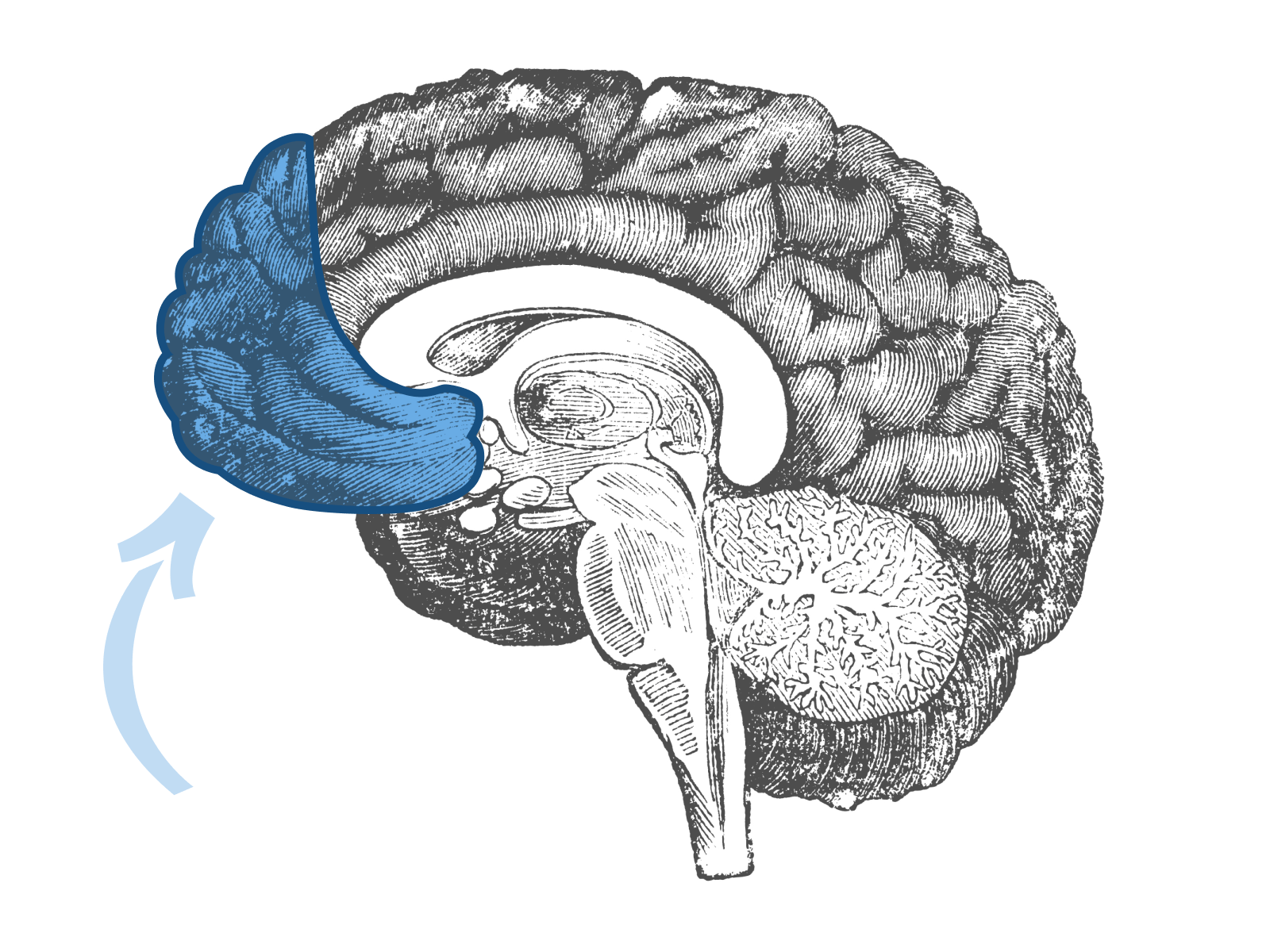

The amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex make up the control panel for bias.

The amygdala fires up for our fears, the hippocampus records our memories, and the prefrontal cortex controls our ability to reason and reconsider.

What part of the brain do you think is responsible for each reaction?

What part of your brain is working here?

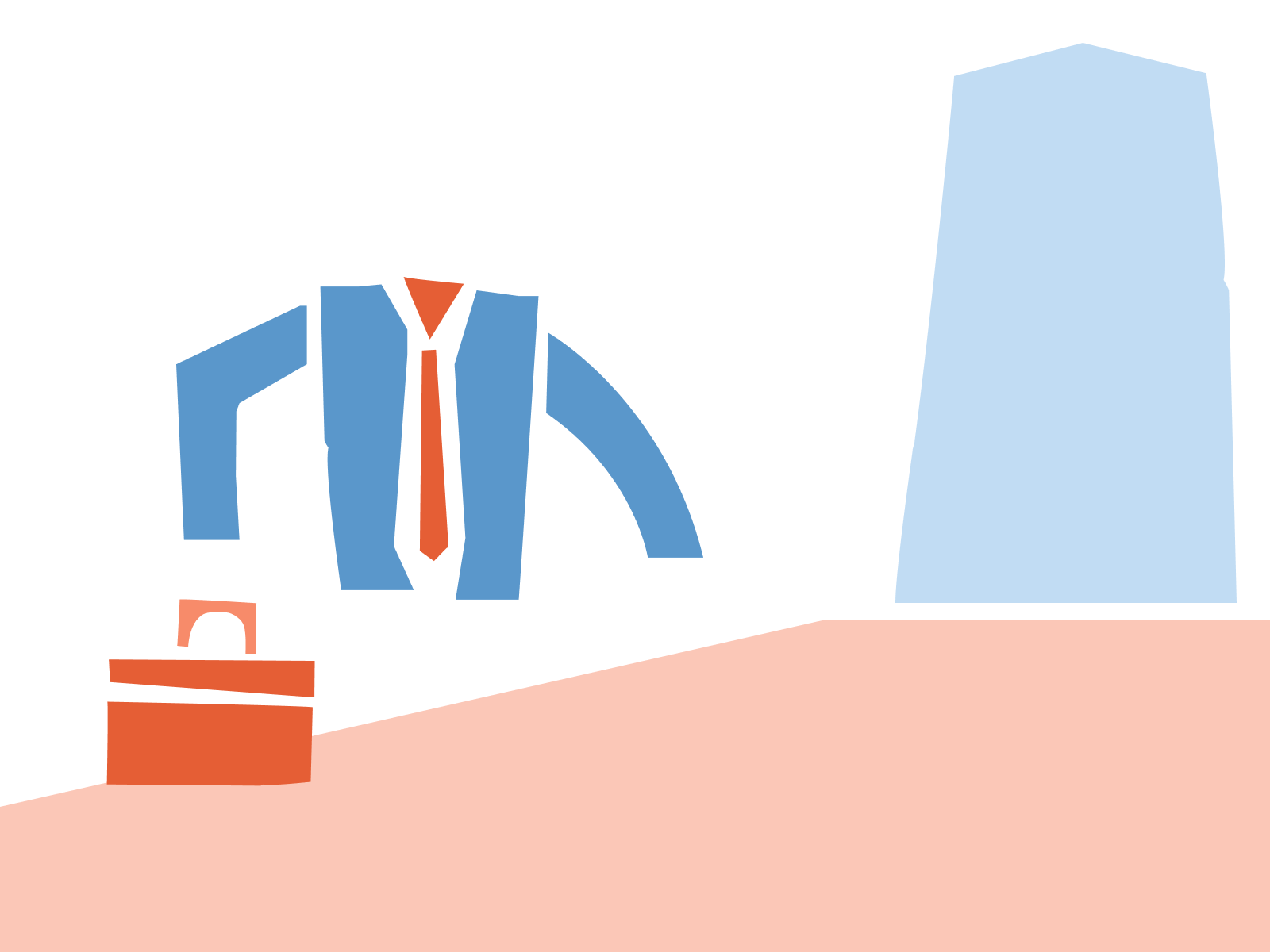

You see a man walk into a fancy glass building. He’s carrying a briefcase and wearing an expensive suit.

Six months later, you see another fancy glass building and assume, “that must be filled with men with briefcases and expensive suits.”

Is it the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, or amygdala?

What part of your brain is working here?

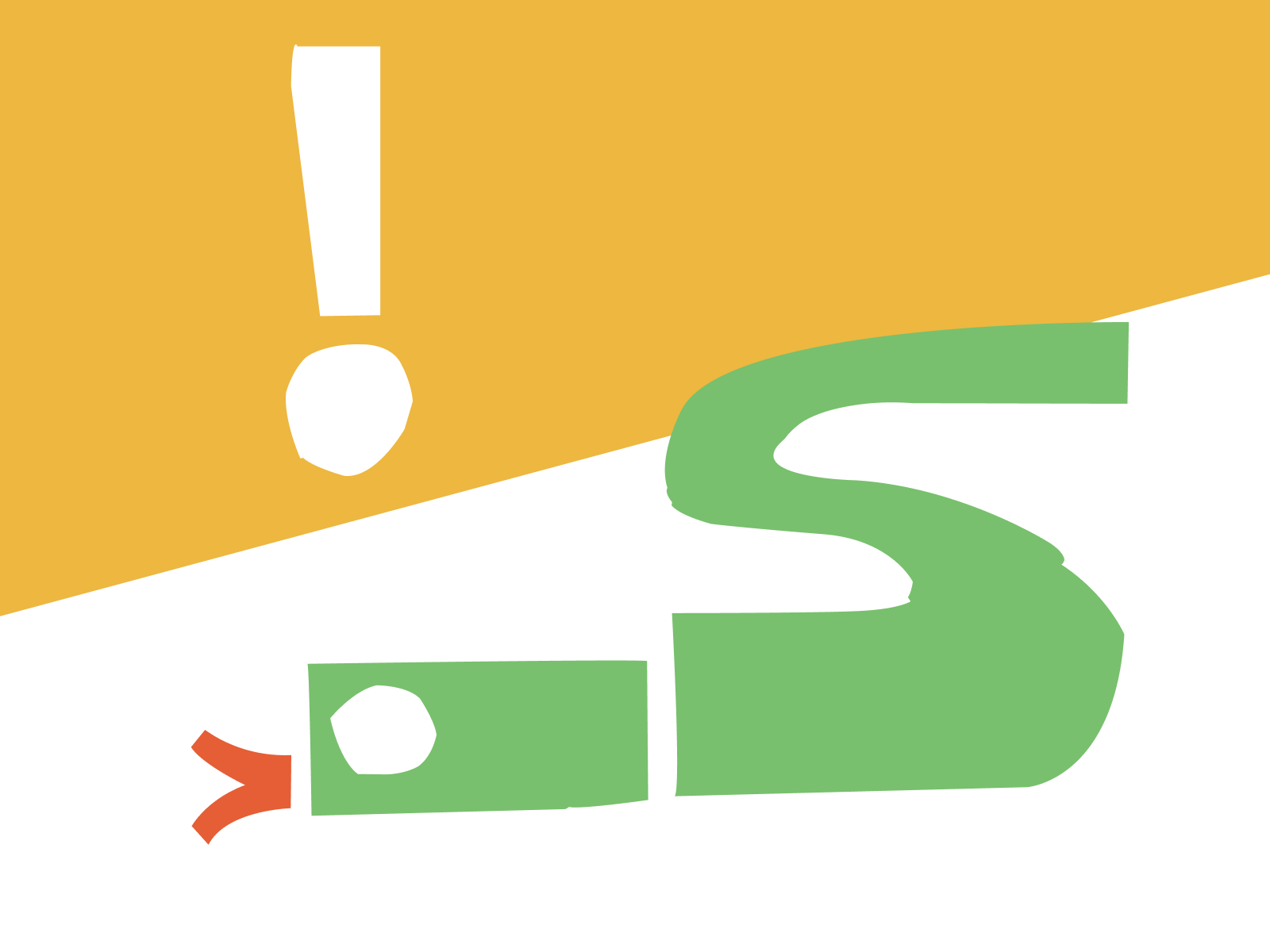

You’re deeply afraid of snakes. Suddenly, a snake slithers into the room.

Your mind makes a snap judgment, immediately sending the message: “Fright! Fear! Flee!”

You run and jump on a nearby table to avoid the snake.

Is it the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, or amygdala?

It’s the amygdala!

This is the “fear center” of the human brain. Fully developed just before a full-term baby’s birth, the amygdala sparks many of our emotions, fears, and impulse reactions.

What part of your brain is working here?

That snake is still in the room. Your amygdala has registered fear and the hippocampus reminded you to be afraid of snakes.

You begin to calm down and realize that you don’t have to panic!

The snake is across the room and, now that you see it more clearly, it doesn’t look so scary after all.

Is it the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, or amygdala?

It’s the prefrontal cortex (PFC)!

This is where the brain settles things.

We can use our PFC to reason through different perspectives, weigh pros and cons, or even revise our previous assumptions about things and people.

Bias is in our brains and baked into our environments from early in childhood.

But having bias does not mean that we are destined to be bad people.

Those same brain processes can sometimes be used for good.

As humans, we can recognize both what we have in common and what we hold as unique differences.

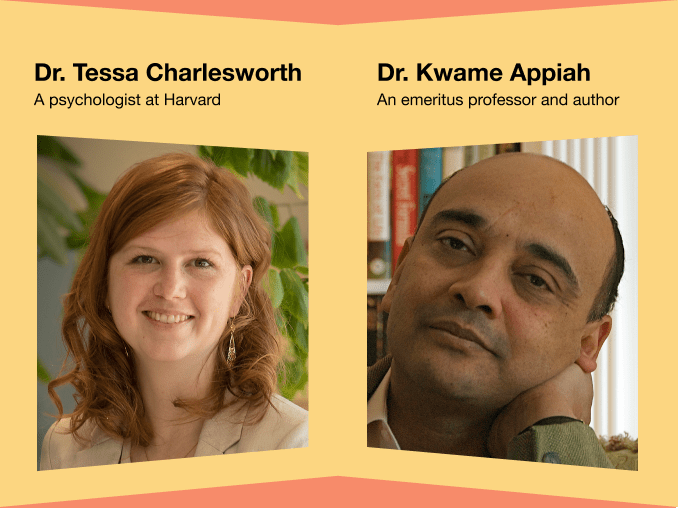

Listen in on a conversation between a young scientist and a celebrated philosopher to learn about the nature of our biases and identities. Dr. Tessa Charlesworth, a psychologist at Harvard, and Dr. Kwame Appiah, an emeritus professor and author, share their thoughts here.

Next SectionBias IRL*(*in real life)

Bias is a process initiated even before we are born. It is a process of learning about the structures and associations embedded in the world around us. But what actually are those structures in the world? Where is bias in real life?

Explore